Charles Marohn May 28, 2024

My hometown of Brainerd, Minnesota, is caught in the housing trap. Most places are. When housing attempts to play the role of financial product while simultaneously serving as shelter, all kinds of ridiculous things happen. This craziness can feel normal. It is not.

“Escaping the Housing Trap,” my and Daniel Herriges’ new book, is now a national bestseller. Thank you to everyone who has obtained a copy for themselves, bought one for a friend or donated one to a local library. And thank you to the hundreds of people who showed up to talk about housing at my recent book tour stops in Virginia and Maryland. There is a real hunger for change when it comes to housing. We are all seeking a way out of this trap.

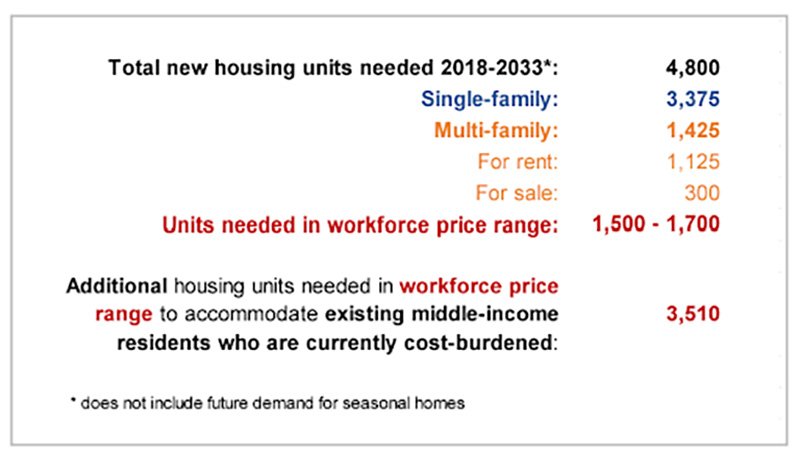

The story here in Brainerd is a familiar one for North American cities. A regional housing study completed in 2020 found that thousands of new affordable units are needed to meet the local demand. That was before prices went supernova during the pandemic. We’re a poor and struggling community, yet we are experiencing housing affordability challenges just as painful as major metropolitan areas.

That desperation for more housing — especially affordable housing — is the backdrop for a proposal to build a new apartment complex in the core of the downtown. As reported in the local paper, the city council approved permits for a 78-unit apartment complex that is being marketed as Eight05 Laurel (my apologies to those who are grammatically sensitive).

If you are an advocate for affordable housing, this is a big leap in the right direction. We are adding 78 units to the most walkable and bikeable neighborhood in town. At least 29 of these will be two-bedroom units (the most urgently needed kind). Sixteen of them will be reserved for families making up to 80% of the median household income and another 31 will be reserved for people making up to 15% more than that median. The remaining 31 will be sold at market rate.

Lots to cheer for if your goal is to make affordable housing. There is dramatically less to be excited about if the goal is to make housing affordable.

While it builds a handful of affordable units, this proposal will do nothing to make housing in the Brainerd Lakes area broadly affordable. In fact, it reinforces the financialized approach to housing, a top-down system that has disconnected housing prices in nearly all American cities from local reality. In that sense, it makes our housing problem worse, and at an enormous cost.

To make this project happen, the state of Minnesota is providing $6.8 million in a workforce development grant. The city is also throwing in almost $3.5 million in a tax increment financing subsidy while waiving $257,400 in utility charges. The Brainerd Lakes Area Economic Development Corporation is adding a main street grant of slightly less than $200,000. On top of that, the Crow Wing County Housing Trust Fund is providing a subsidized 20-year loan of $1.3 million.

That’s around $12 million in subsidies. For 78 units. That is a subsidy of $154,500 per unit in a city where the median home price is $210,000. No matter where your heart is on building affordable housing, you have to acknowledge that there is no way this approach scales.

It is hard to imagine Brainerd repeating this effort with another project of this scope, let alone enough projects to get the thousands of units our studies suggest are needed. Spending time and resources on an approach that doesn’t scale — has no chance of scaling — is what leads to the feeling of helplessness many local leaders attest to when it comes to housing.

This project is what moving heaven and earth looks like for a local government. It is the kind of thing we see cities of all sizes attempting to do, all over the country. Yet, in the scope of the affordability challenge we face, it is nothing. Sisyphus laughs at us.

We have to move beyond the narrow, almost futile task of making affordable housing and start working on the broader and more meaningful effort of making housing affordable.

The term “housing trap” is a way to explain the financialized craziness that makes housing prices more responsive to macroeconomic capital flows than local supply and demand dynamics. The reason housing prices are crazy everywhere at the same time isn’t because every local market has the same supply constraints. Supply constraints exist in many markets, sure, but the story of housing affordability is primarily a financial one.

We financialized the housing market for expedient, even righteous, reasons. The consequence of this approach is that today’s housing acts more like a financial product than a shelter for a family.

Local governments won’t change our country’s macroeconomic environment. No city can decouple bank reserves from mortgage-backed securities. No mayor will outlaw the thirty-year mortgage. There won’t be a protest movement forcing public employee pension funds to divest from the housing market. For most housing products purchased by most people, we have to deal with the system we’ve been given.

Yet, local officials are not helpless. Part of the craziness of the current system is that there is no local mooring for housing prices. There is no entry-level product providing an anchor to upwardly accelerating home prices. There is no housing product that is responsive to local supply and demand dynamics.

Stop feeling helpless! We can create this product.

We can take that unused fourth bedroom in the single-family home and turn it into an accessory apartment. We can take that unused space in the backyard and allow the homeowner to build a backyard cottage. We can take that empty lot and get a 400-600 square foot starter home built on it. We can do all these things quickly, affordably and at a scale sufficient enough to impact prices locally.

Cities can make it easier to build these kinds of products through regulatory reform. They can cultivate a cadre of incremental developers to do this kind of work. And, perhaps most importantly, they can help finance these entry-level units, providing local competition to the federally subsidized, Wall Street-based housing market. They can do this all at scale and at very little, if any, cost to local taxpayers.

As I continue to travel around North America as part of the “Escaping the Housing Trap” book tour, the team here at Strong Towns is assembling a toolkit of strategies and approaches cities can use to escape their own housing trap. You can stay tuned here for future updates on that or, if you’re ready, you can sign up to become a member of Strong Towns and go deeper by participating in a Local Conversation.

And if you’re a public official or other local leader ready to change the housing story in your community from helplessness to positive action, we’re ready to help you. Send us a message and we’ll set up a meeting to help you get started.