The Answer To Making Cities More Family-Friendly? Courtyards

New housing experiments with courtyards show that this age-old design approach can still deliver for cities struggling to provide homes for families.

October 31, 2024 at 7:30 AM CDT

Bloomberg News has won the 2025 Pulitzer Prize for Criticism, with a collection of essays for Bloomberg CityLab by contributor Alexandra Lange. Read the series here.

The population of children under five is shrinking across the US. That group has decreased most rapidly in big cities: 14% in Los Angeles County, 18% percent in New York City and 15% percent in Cook County, Illinois, which includes Chicago.

This is bad news for the diversity and stability of cities, which are improved by the amenities that families seek — parks, public libraries, safe streets. It’s also discouraging for families who prefer to live in the city or don’t have the option or desire to move to the car-dominated suburbs. Any effort to retain families has to start with housing, their primary expense.

That one weird trick for making cities more family-friendly? We’ve known it for decades: It’s the courtyard.

As advocate Alicia Pederson wrote in the Chicago Tribune earlier this year, “To compete with the suburbs, American cities should try an urban typology that has kept families in European city centers for millennia.”

Sign up here for Design Edition, CityLab’s newsletter on architecture and the people who make buildings happen.

While Europe can claim centuries-old courts, America dabbled in them for decades, before the suburbs became the dominant housing type of both government subsidy and political propaganda.

Courtyards don’t have to belong to the past. While textbook examples in brick and stone are lovely — and still home to thriving communities — contemporary architects are making courts in all sorts of materials, and for all types of housing, from apartments to townhomes.

One of the first influential figures to advance the idea of the courtyard as the ideal urban type for families was Henry Darbishire, the mid-19th century English architect. His first patron, Angela Burdett-Coutts, was inspired by Charles Dickens and his novels of the urban poor to apply her wealth to reformist housing. “Nurturing the family and protecting children from the street was a huge part of the logic — turning the city inward,” says Matthew G. Lasner, housing historian and the author of High Life: Condo Living in the Suburban Century.

Architects and philanthropists quickly embraced an easily replicable courtyard model, with a single entrance on the street and interior vertical access off a planted court. The concept came to America in the 1870s via developers like Alfred Treadway White, responsible for the Cobble Hill Towers in Brooklyn. In the 1920s, more reformist developers — including everyone from the Rockefellers to communist unions — constructed many more of these courtyard projects.

As architecture critic John Taylor Boyd wrote in 1920 of the Linden Court complex in Jackson Heights, the courtyard’s “benefits are apparent when it is remembered that the streets are the only playground of New York children, including the children of the rich; even the luxurious Park Avenue apartment houses make a poor showing in this respect.”

New policies, and a better understanding of how families thrive in urban environments, could make courtyards the housing of the future once again.

Courtyards Across the Eras

When you’re talking courtyards in America, it’s hard to avoid Sunnyside Gardens. Not only does the Queens community remain one of New York City’s best neighborhoods, but it was home to one of America’s best critics, who made his affection clear.

Lewis Mumford was one of the first residents of Sunnyside Gardens, completed in 1928, and constantly returned to its balance of private and public space, building and garden, in his analysis of other lesser New York City housing options. In “The Plight of the Prosperous,” published in The New Yorker in 1950, Mumford takes aim at the new white-brick residential buildings “that have sprung up since the war in the wealthy and fashionable parts of the city.” While new low- and middle-income housing projects like his own “provide light and air and walks and sometimes even patches of grass and forsythia,” these other private buildings, clustered in uptown rich neighborhoods, lack multiple exposures, outdoor space, cross-ventilation and quiet. He was leading a much richer domestic life in Queens.

Clarence Stein and Henry Wright were the primary architects and planners behind Sunnyside Gardens, with Marjorie Sewell Cautley the landscape architect; all three would subsequently collaborate on Radburn, New Jersey, the “town for the motor age” that in fact applied these communal principles for a result that we would now call transit-oriented development.

The planners’ primary insight, in both the city and the suburbs, was to prioritize protected, communal open space over private yards or interior amenities. The courts, or courtyards, could be much larger if not subdivided by owner, and even in areas with public parks, having play space (and play companions) directly outside your door was a huge amenity. That meant no scheduled playdates, no interrupted housework and only minimal supervision required, since kids didn’t have to cross a street to find friends.

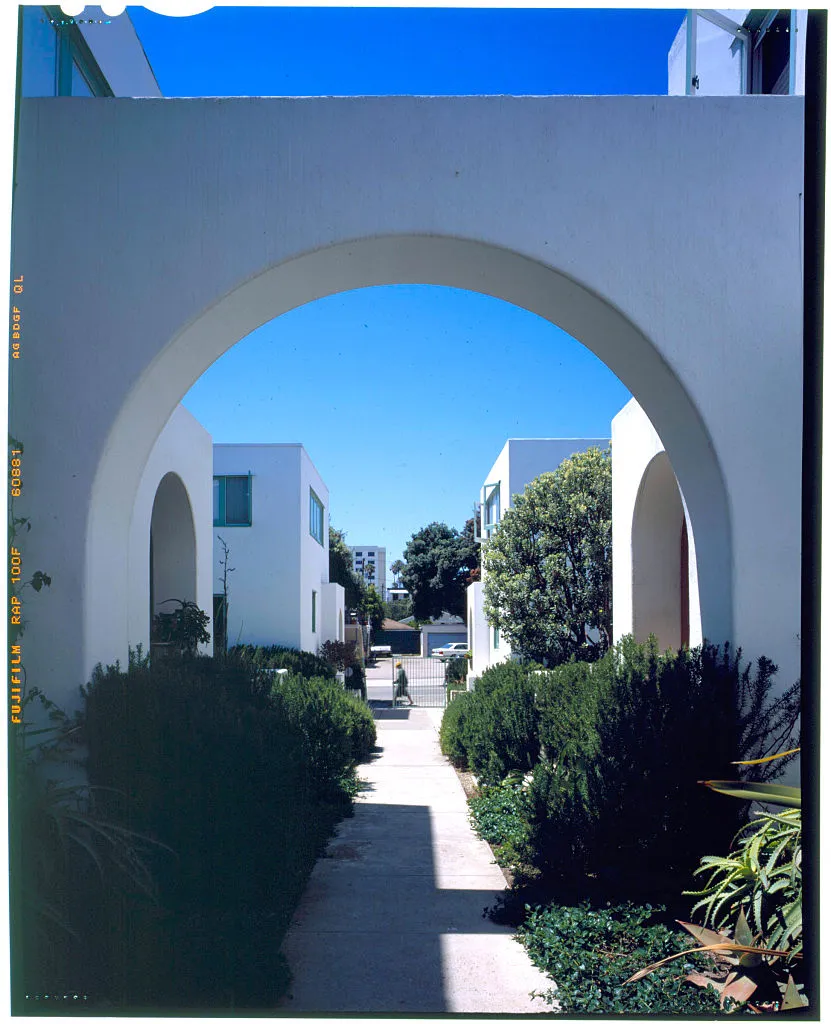

On the West Coast, the courtyard evolved a little differently: surrounded by lower density, semi-detached houses with, eventually, a swimming pool in the center instead of a lawn. Irving Gill, considered the father of California modernism, designed prototype bungalow court in Santa Monica in the teens, with parking out of sight in the back and doorstep gardens. On tighter sites, U-shaped buildings with Spanish- and Italian-influenced architecture featured tiled fountains at center court.

In the postwar era, multi-family housing, like its single-family contemporaries, embraced the pool. Fans of the 1990s-era soap Melrose Place will be familiar with this type as a haven for swinging singles, but one prominent real-world example — Parkview Village West, built in Torrance, California, in 1964 — “was initially marketed to families with children,” Lasner says. “It had the pool, a rec room, a supervised children’s center, a teen center. But it failed. Families in 1964 in Los Angeles were not interested in this more communal life.”

In 2024, the marketplace looks a little different. A recent op-ed in the Los Angeles Daily News bemoaning the city’s loss of families mentions many of these low-rise, good-weather alternatives: “the city’s beloved Spanish-style fourplexes, bungalow courts, and stylish apartment buildings like Hancock Park’s El Royale are a product of a time when LA homebuilding was relatively unrestricted.”

Over subsequent decades, the appeal of the courtyard plan never faded: Pushing the building mass to the edge of the lot, providing a balcony, deck or minimal yard for every resident, and creating a landscaped court in the center of the building appear in designs from the 1970s through the 2000s.

Theorist Christopher Alexander even gave a name to this phenomenon in his classic 1977 study of building patterns, A Pattern Language. Building pattern number 68, “Connected Play,” spells it out. “Since the layout of the land between the houses in a neighborhood virtually controls the formation of play groups, it therefore has a critical effect on people’s mental health. A typical suburban subdivision with private lots opening off streets almost confines children to their houses,” he writes. “Children need other children.”

Despite the fact that these courts are still in demand, most are now functionally illegal to build, thanks to restrictive zoning laws and building codes. “Footnote is, I stopped by [Parkview Village] a few years ago, and there was a giant bouncy castle and a pool full of screaming kids,” says Lasner.

Courtyards to the Future

For a number of burning contemporary housing debates, courtyards are an answer hiding in plain sight.

In 1993, as part of Vienna’s effort toward “gender mainstreaming” public policy, the city held a competition for an apartment complex designed by and for women. The result, Women-Work-City was, unsurprisingly, 357 units of courtyard housing. As The Guardian wrote in 2019, “It was characterized by a woman’s perspective at every level: from pram storage on every floor and wide stairwells to encourage neighbourly interactions; to flexible flat layouts and high-quality secondary rooms; to the height of the building, low enough to ensure ‘eyes upon the street.’” The complex also included an on-site kindergarten, doctor’s office and pharmacy.

Courtyard housing also offers a powerful salve for the housing affordability crisis. Most courtyard housing is also “missing middle housing” — defined as multifamily projects ranging from accessory dwelling units and duplexes to mid-rise apartment buildings — most of which could easily be arranged around common green space. As the Regional Plan Association reported this June, most missing middle building types “are already part of New York City’s current housing stock, but regulations broadly prohibit new ones from getting built.”

Courtyard housing formally aligns with a burgeoning YIMBY movement to legalize point-access blocks. Most apartment buildings in the US are required by law to use double-loaded corridors: hotel-style hallways with units on each side and stairways at both ends. The dual-stairwell building code requirement limits the size and shape of apartment units. Advocates in multiple states are pushing to allow buildings of up to five stories to have a single stair-and-elevator combo, which would enable a better mix of units sized for families, and more daylight and better cross-ventilation between them. Single-stair access can also provide a sense of community: Residential colleges, another longstanding form of courtyard housing, frequently organize activities by “hall” or “entryway,” governed by the doors opening off a single-stair hall.

Even without legislative change, creative designers and developers across the country are turning to the court to disrupt traditional housing patterns. Brooklyn architects SO-IL have made casual encounters, shared outdoor space and even pastels the hallmarks of several residential projects with developer Tankhouse. Their collaboration started with 450 Warren, a condominium in Brooklyn’s Boerum Hill with an open-air court framed by wire mesh. A project in Fort Green, 144 Vanderbilt — the pink building — includes more of the same, layering small private outdoor spaces, exterior circulation and larger common gardens. The innovation over the past is the multiple levels across which run-ins with neighbors and greenery can take place.

“It was clear from the beginning that families were at the center” of building community, Tankhouse’s Sebastian Mendez told me. “A building can have communal spaces where kids can play without one having to worry about where they are.”

For Brunson Terrace, a 48-unit, 100% affordable project which opened in Santa Monica in 2024, Los Angeles architects Brooks + Scarpa left its modest ground-level courtyard to the kids, with bright climbing structures surrounded by organic planting beds. Exterior bridges, stairs and walkways provide access to quieter seating areas. They also make circulation more fun and functional: laundry rooms are located adjacent to the stairs, so caregivers can do chores with an ear out for their kids playing below.

Providing services, not just housing, is key to the Tapestry Block, an affordable housing project for Denver being developed by the nonprofit Colorado Health Foundation. The Denver-based architecture firm Livable Cities Studio outlined a vision for the project that includes a medical clinic, child care and spaces for after school and cultural programming, all built around a half-acre courtyard.

“When people have families with children, the home is important, but equally important are the people who are there with you,” says Livable Cities president Meredith Wenskoski. “Your neighborhood is crucial – that resource-sharing, places for gathering and events.” She says it’s important to think long-term: The Tapestry Block courtyard has a small playground, but they also want to provide teen hangout space. “You want families to grow and stay.”

Bay State Cohousing, a 30-unit development outside Boston, has common amenities as part of its charter, including a shared kitchen and activity rooms. But the pastel, clapboard complex, intended to blend in with single-family neighbors, also forms a U around a southwest-facing courtyard, with outdoor circulation providing plenty of opportunities for casual run-ins with the neighbors.

“The courtyard is a nested boundary that allows interaction with other children, and more importantly, with other adults who become a kind of network,” says Jenny French, whose firm French 2D designed Bay State. “In an urban setting, the barrier that the contemporary parent has to letting their child out the door, thinking about the car-dominated city where they are unable to play in the street – the courtyard is a natural alternative.”

French, who has also been coordinating the housing studio at the Harvard Graduate School of Design for seven years, can’t help but extend these design observations into the cultural and political spheres. Everyone talks about loneliness in America for people of all ages. For teens and seniors alike, French sees a solution. It’s one we’ve had all along: “Could a courtyard house actually be the friendship apparatus we need?”